Deforming the Database: A DH Project on Interactive Fiction

Posted on May 3, 2021

[Counterfeit Monkey] highlights the fact that whatever else IF is, it is mostly text, and that the imaginary it invites us to inhabit is one that is almost exclusively produced through language games played by the interactor through conversations with the author, the software, and the platform.

Scott Rettberg, Electronic Literature

There is one other important result. A deformative procedure puts the reader in a highly idiosyncratic relation to the work. This consequence could scarcely be avoided, since deformance sends both reader and work through the textual looking glass. On that other side customary rules are not completely short-circuited, but they are held in abeyance, to be chosen among (there are many systems of rules), to be followed or not as one decides.

Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann, "Deformance and Interpretation"

At the crossroads of literature and games, Interactive Fiction (IF) has long attracted scholars of literary studies, game studies, and computer science. Also known as “text-based adventure games,” IF preceded graphical home computer games, taking place in the textual interface of the command line. The computer provides a textual description of the game world and the player inputs commands through a text parser in order to direct the protagonist through this textual environment. Underneath, there’s lots of code, but on the surface, there’s only the ebb and flow of natural language, of text.

Almost all of IF criticism focuses on the code below (Pias) or the player’s interaction (Aarseth) or the code implied in the player’s interaction (Douglass)–but what if we directed our attention instead only to this textual surface, fishing it out from the source files and leaving (or banishing) the code and player in the depths?

As apparent in the breakdown of the sea metaphor, such a project confuses the conventional understanding of surface and depth in relation to new media technologies and their interfaces, in which ostensibly the content exists on the surface and the code, hardware, voltage signals, etc. in the depths. Instead, here, the emphasis is not on the content that emerges to the surface through actual play, but on the excavation of potential content from the depths of the code. Rather than a narrative algorithmically constructed from the game’s database, this project will analyze the database itself, in all its rich potential.1

Put simply, what if we machine read the databases of these texts in the same way we machine read novels, stories, poems, newspaper articles, and other documents?

From one perspective, this project appears as an attempt to bypass the “interactivity” of interactive fiction in order to access the database beyond the parser. Such a conception implies removing the player and code, and thus play and interpretation, in order to get at the totality of the text. But such totality is always elusive, and it’s a common misunderstanding or misrepresentation of the digital humanities to perceive its methodologies as totalizing. Instead, I perceive this project as a substition of forms of interactivity, replacing the IF parser with algorithms common to the digital humanities (topic modeling, concordance analysis, word embedding, named entity recognition, and social network analysis). Rather than foregoing interactivity and interpretation, the digital analysis of IF shifts these processes to different levels of scale (hundreds of texts rather than one) that retreive new features of IF from the database, admittedly and deliberately obscuring some aspects of the games (e.g. reader response) in order to reveal those as yet illuminated.

But what exactly is the “interactivity” of interactive fiction? Several scholars of the field critique or outright despise the term. For Claus Pias, “the term ‘interactive fiction’ should be inverted, for what we are dealing with is in fact a fiction of interactivity” (132). More scathingly, Espen Aarseth exposes the term as ideologically motivated, implying that humans and machines are on the same level while thoroughly devaluing the role of the human and endowing the machine with a “magic power” (48). For him, “[Academic use of the term] shows how commercial rhetoric is accepted uncritically by academics with little concern for precise definitions or implicit ideologies.” In order to avoid such pitfalls while still playing on the term “interactive,” I wish to delineate the types of interactivity in IF and digital methods.

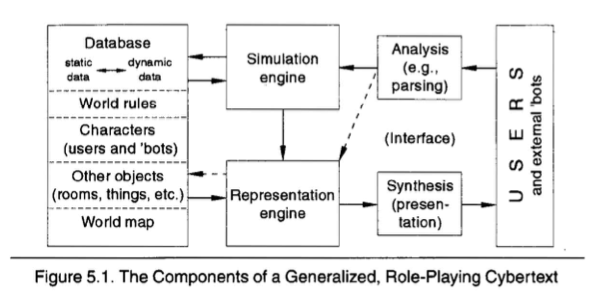

“This model is best suited to describe indeterminate cybertext. In determinate cybertext (e.g., Adventure), the three functions-simulation, representation, and synthesis-might be better described as a single component.” (Aarseth 104)

In this figure, Aarseth provides a flow chart for understanding the several interactions at play under the hood of the IF terminal. The user issues commands to the parser which renders them computationally comprehensible for the simulation and representation engines that variously interact with the game’s database through a series of feedback loops before outputing the result to the user via the interface. More simply, Nick Montfort identifies the two essential components of IF as the parser (represented by Aarseth’s Analysis box) and the world model (everything on the far left of the diagram) (viii). With either the simple or complex diagram, it’s clear that the “interactivity” of interactive fiction refers not only to the human/user interacting with the machine, but also various computational levels interacting with each other. As such, we might think the interactivity of IF, in a Latourian sense, as a distribution of agency across human and nonhuman actants.

DH functions similarly. While there is significant variation in methods of analysis and visualization (perhaps too much to produce an essential diagram as above), they all share in the delegation of much of the processing and visualization of textual features to newly developed or pre-existing algorithms. In a sense, performing a digital analysis of IF means swapping out the middle of Aarseth’s diagram for some of the more common DH tools, and thus providing a new way for the users to interact with the work’s database.

In so doing, this interaction changes from the input of textual commands typical of IF (e.g. “examine desk,” “walk north,” “take lamp”). Instead, the user interaction might resort to a plug-and-chug variety of DH, merely inputing a selection of text (via a GUI or CLI) and interpreting the outcome. Or it might result in the tinkering with already existing code to zoom in on different features than currently programmed. Or it could result in the production of a totally new means of algorithmically analyzing text (albeit unlikely, given my programming experience).

Further alterations in interaction occur at the level of the interface. In addition to replacing the algorithmic processing of the database, DH methods provide new ways of visualizing the output. Rather than IF’s purely textual output in the command line, digital tools allow for a variety of visualization techniques, from simple charts and graphs to complex distributions in multidimensional space. Such visualizations produce a second order form of interactivity, in which the user not only processes the database and creates visualizations from the metadata but can also interact with the data visualizations (adjusting parameters, navigating multidimensional representations, performing clustering functions, etc.). In so doing, the digital analysis of IF might expand the range of interactivity to the point where it ceases to succumb to Aarseth and Pias’ critiques of the term.

But the project doesn’t solely intervene in the field of IF criticism–it allows us to look askance at both IF and digital methodologies. Most digital analyses of literature entail the creation of a database from materials not intended or designed for such an environment. Books, for instance, must be digitized, reduced to text files, and collected as a corpus before analysis. In contrast, the text of IF is born digital, only ever existing within the environment of a database. Instead of wrangling non-database forms into a database, the digital analysis of IF requires the excavation of many databases (one for each game) and the conglomeration of these into a larger corpus. In so doing, this project sidesteps some common concerns associated with digital analyses (e.g. ignoring the materiality of books or other media) while raising others, such as the integrity and boundedness of the individual database. What happens when databases mix and blur, when data becomes so heterogeneous? What implications might an exploration of database mergers and consolidations have on the field of the digital humanities? Do born-digital databases have the sanctity of the well-bounded book, or does the nature of the digital environment render such notions obsolete?

But, for now, I shall leave these questions hanging only to fall down in my next blog post.

References

Aarseth, Espen J. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. UK ed. edition, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Douglass, Jeremy. Command Lines: Aesthetics and Technique in Interactive Fiction and New Media. University of California, Santa Barbara, 2007. ProQuest.

McGann, Jerome, and Lisa Samuels. “Deformance and Interpretation.” Poetry & Pedagogy, edited by Joan Retallack and Juliana Spahr, Palgrave Macmillan US, 2006, pp. 151–80. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1007/978-1-137-11449-5_10.

Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction. The MIT Press, 2005.

Pias, Claus. Computer Game Worlds. Translated by Valentine A. Pakis, 1 edition, Diaphanes, 2017.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. 1 edition, Polity, 2019.

-

Montfort compares IF to the Oulipo project in this way: “In examining this aspect, I rely on the usual tools for the formal analysis of stories (the narratology of Gérard Gennette, Gerald Prince, and others), with consideration of the nature of IF as potential narrative rather than narrative. It is the effect of the narrative in the process of being generated that is important, after all, not the quality of the text that is output when the session is over, and not the effect of any post hoc reading of that output text” (14). Obviously, my project aims to challenge Montfort’s emphasis on the “narrative in the process of being generated” to the exclusion of all other means of approaching IF. ↩︎