Hacking Games: else Heart.Break()

Posted on December 10, 2018

[This post takes off from the previous “Back to the Screen?” to assess the relationship between critical infrastructure studies and what I am tentatively identifying as a “critical hacking” genre of video games.]

In my previous post “Back to the Screen,” I examined the impetus in game studies (and media studies writ large) to “go deeper,” and explore the ostensibly “hidden” layers of games–the software and hardware underlying the content. For these scholars, content functions similar to ideology in orthodox Marxism, hiding or otherwise obscuring the real processes and relations of, in this case, the gamic world. While this may very well be the case for most games, this post considers a “critical hacking” genre of video games in which, far from hidden, code and other computational infrastructures appear front and center on the screen itself. While perhaps starting as merely representations, the development of this genre (a history of which will require a future blog post) appears to reach its apotheosis in games like Quadrilateral Cowboy and, especially, else Heart.Break(), in which the user interacts with fully functioning computational infrastructures that blur the divisions between content and medium, representation and real. Examining else Heart.Break() as a case study, this post explores the theoretical implications and potential politics of a game that opens up its own infrastructure, inviting in the player as co-constructor.

else Heart.Break(): An Overview

else { Heart.break } is a game about being able to change reality. It is set in a mysterious world made up of computers and their code; a place where bits have replaced atoms. The player – who is assumed to have no previous knowledge about programming – gets access to the code and is taught by other characters how to modify it. As the story unfolds the possibilities of what can be reprogrammed, hacked and controlled increases greatly. Eventually the inner parts of the gameplay code are revealed and the barrier between our own world and the game starts to dissolve.

The idea is to create opportunities for truly creative gameplay that goes beyond the kind of puzzle solving and stats improvement normally seen in games. Ideally it even allows the player to free herself from the designer of the game!

Game Designer Erik Svedang, “else {Heart.break()}”

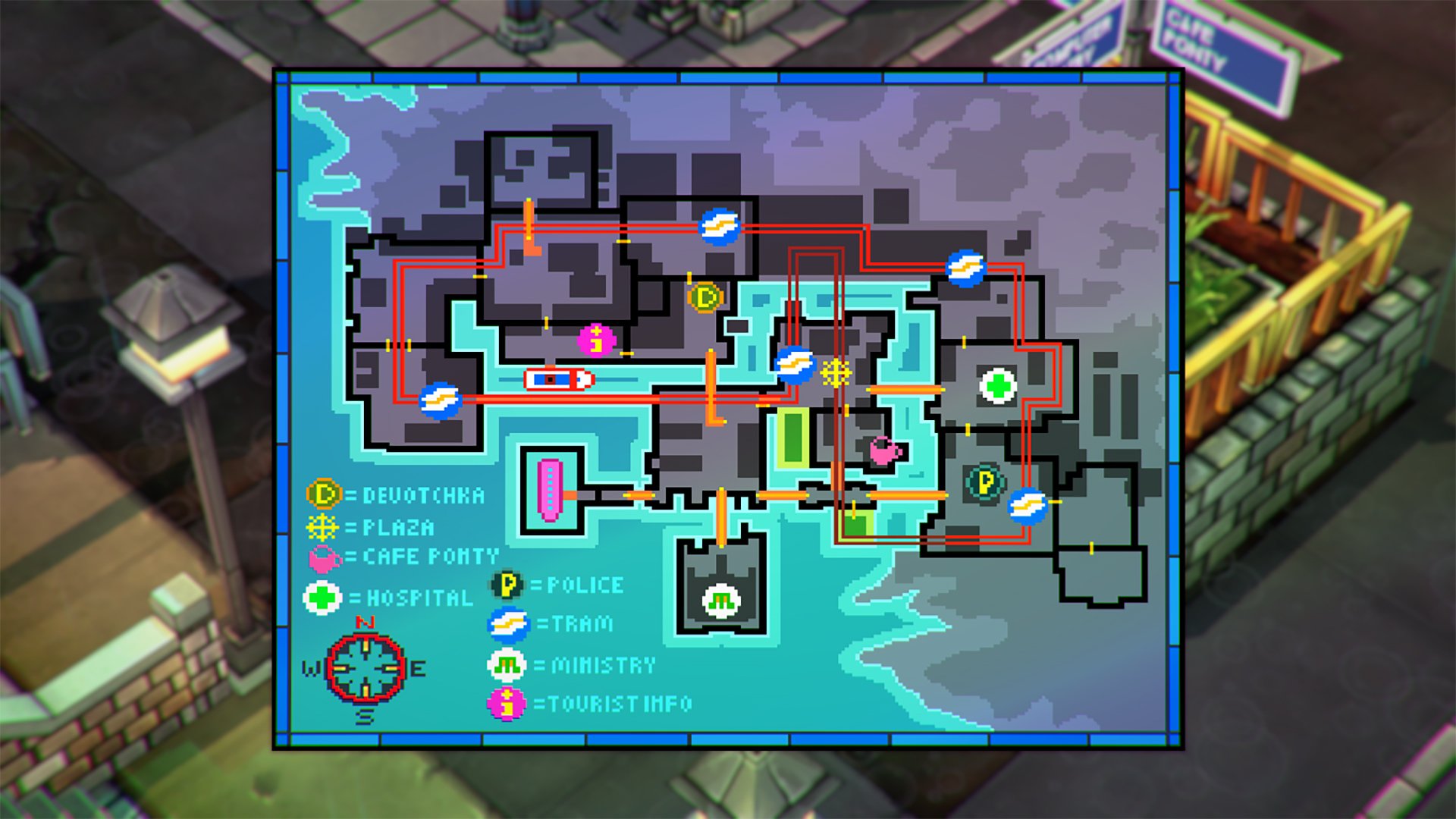

In else Heart.Break(), the player protagonist Sebastian accepts a job as a soda salesman in the as yet unfamiliar town of Dorisburg, Sweden. Arriving by boat, the player is left to explore the town without any navigation devices aside from street signs and (if found) a simple static tourist map. From here, the game at least somewhat expects you to interact with other characters, make friends, and, of course, join a cyberpunk hacker collective to fight off the ambiguously nefarious “Ministry,” which has digitized the infrastructure of the city for the purpose of mass surveillance.

Although the game certainly has a main quest/narrative, all tasks can only be found via the player’s innate curiosity. Within this open world environment, almost all interactions can be avoided, except for the exploration of the city’s infrastructure, including even and eventually the code through which it is generated.

But this cannot be achieved without a “Modifier,” which enables the characters to hack into not only computers but all of the accessible objects in the game. And, as many players have experienced (myself included), obtaining a modifier can take hours. Without this tool, the game functions as a pre-digital derive–a throwback to the Situationists’ program for natigating cities–as the player drifts through the streets, plazas, houses, gardens, mines, railways, and harbor of Dorisburg. True to cyberpunk generic conventions (e.g. Neuromancer’s Case locked outside of the matrix), this simulated version of meatspace can be drawn out and dull, exacerbated further by the game’s point-and-click features and required sleep algorithm. Fortunately, these features are hackable.

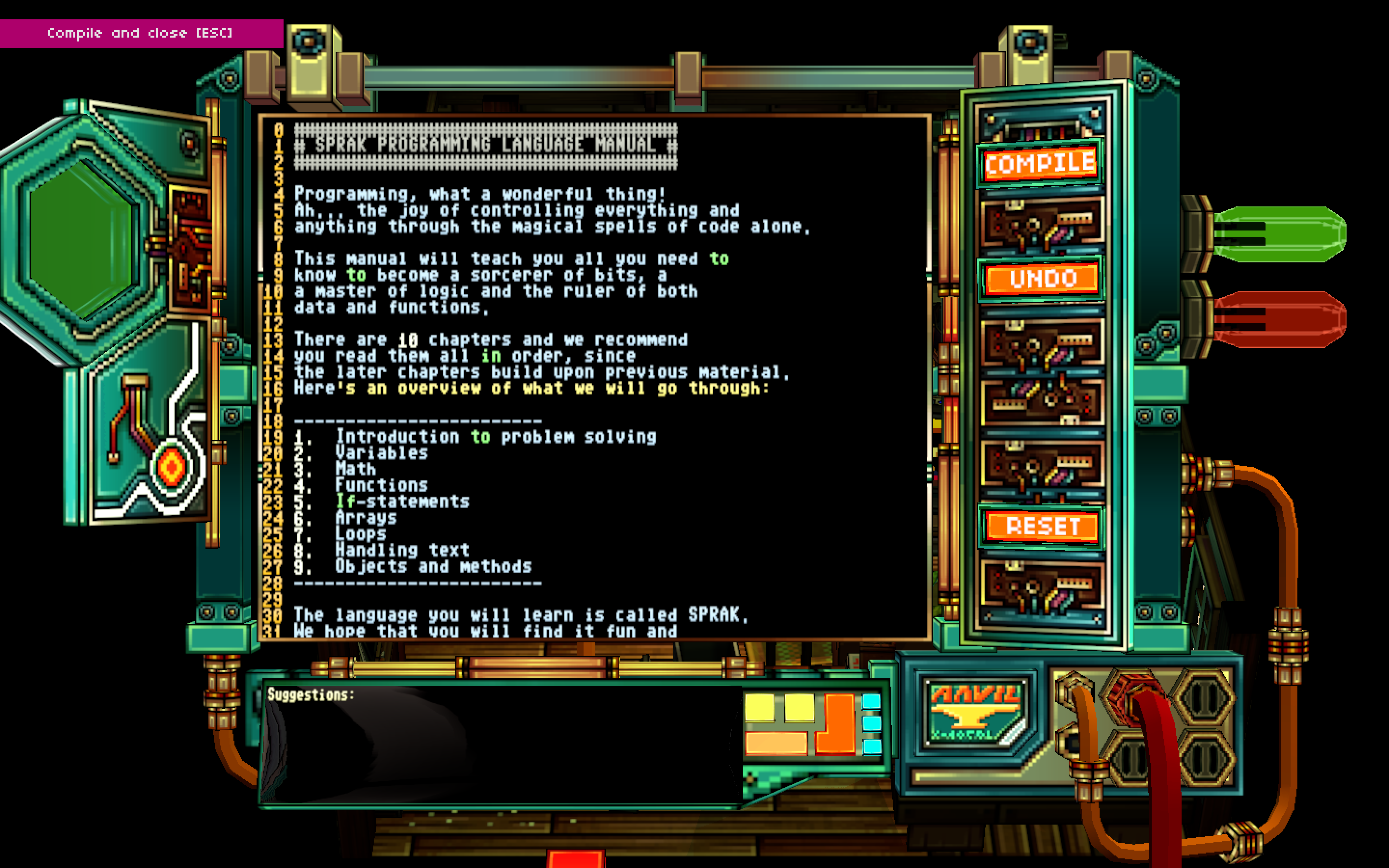

The game features its own programming language called SPRAK (Swedish for “language”), a manual for which exists on a collection of 10 in-game floppy disks (fortunately all located within the same room).1 Armed with a modifier and a working knowledge of SPRAK, the player can re-program any of the accessible objects in the game, whether to give a beer the effects of a cup of coffee (by replacing the DRUNKENNESS() function with a negative SLEEPINESS() function) or to create vast networks (even within the same drink) controlling the movements of characters, the flow of capital, the weather, the objects in rooms, etc.

As if that weren’t enough, else Heart.Break() also encourages hacking the game itself.

. Author: Lstor.](/frettingsontheblank/assets/img/ehb_meta.png)

Although I’ve yet to explore this feature in-depth, both Lstor’s guide and the uncommonly accessible and human-readable nature of the game’s file structure suggest that the game invites the player to analyze, reconfigure, and build within its own infrastructure.2

What kind of game is this?

if/else Heart.Break(): two interpretations

As mentioned in my previous post, current game studies scholarship assumes the obfuscation or blackboxing of the game’s functioning, thus requiring the critic to delve deeper and explore the software and hardware levels of the game with an already acquired technical knowledge of computation. But what do we do with a game that wears its code on its sleeve and actively teaches the player (assumed to have no technical knowledge) how to understand and reconfigure it? Rather than following the “Deeper! Harder!” impetus, what might we find at the level of the screen–no longer the screen of “screen essentialism,” but that of an infrastructural overlap of code and content?

It seems to me that the game offers two contrasting, and perhaps equally plausible, possibilities for critique: (1) else Heart.Break() functions as the exemplary model for Alexander Galloway’s “control allegory” in which the seemingly emancipatory aspects of the game merely conceal our new oppression under informatics of control; and (2) else Heart.Break() functions as a form of tactical media that intervenes and disrupts commercial video games’ fantasy world of distraction and passivity through meta-ludic techniques that provoke participation in the critical building and reconfiguring of our digital infrastructures.

On the one hand, we might think of else Heart.Break() in relation to games that position the player as a God-figure, omniscient and omnipotent within the gameworld. As in Sim City or Civilization III (from Galloway’s book), the player acquires control over the other characters, as well as many other aspects of the fictional world. For Galloway, this ostensible power and freedom represent the paradigmatic transition from Foucauldian disciplinary societies to Deleuzean societies of control.

Video games are allegories for our contemporary life under the protocological network of continuous informatic control. In fact, the more emancipating games seem to be as a medium, substituting activity for passivity or a branching narrative for a linear one, the more they are in fact hiding the fundamental social transformation into informatics that has affected the globe during recent decades. […] A game’s celebration of the end of ideological manipulation is also a new manipulation, only this time using wholly different diagrams of command and control. (106)

From this perspective, else Heart.Break()’s seeming liberation through code only obscures the player’s manipulation via the informatics of control. Unlike disciplinary models, informatics enables a wide variety of choice and flexibility, but rather than freedom, this seeming variety signifies merely a multiplication of means of control. For Galloway, these means are the unseen algorithms underlying the game. Playing the game is playing these hidden algorithms.

But, as already and extensively observed, these algorithms are anything but unseen in else Heart.Break. Does revealing the algorithms of control facilitate yet another illusion of freedom?

Possibly, but perhaps only because the informatic model seems capable of rendering any liberatory practice suspect. More likely, the game seems to suggest a particularly infrastructural form of Brechtian alienation, in which critical distance and disinterested observation are replaced by critical immersion and active (re-)construction of the text itself and the world in which it circulates. Perhaps Galloway’s declared end of ideology critique signifies not just the transition to informatics of control, but also the emergence of new artistic methods for subversion that elevate critical immersion and construction over ideology critique’s critical distance and deconstruction.

I envision this as in line with theorizations of tactical media, in which distance no longer functions as the foundational principle of critique. Instead, as Alan Liu distinguishes it, such methods are “tactical rather than strategically pure because their very potential for critique arises from dirty-hands proximity to, and sometimes even partnership with, their objects of critique.” Or, as Rita Raley theorizes, “tactical media comes so close to its core informational and technological apparatuses that protest in a sense becomes the mirror image of its object, its aesthetic replicatory and reiterative rather than strictly oppositional” (8).

From this perspective, else Heart.Break() may not only appear stylistically similar to Galloway’s informatic games, but actually mimics or perhaps even shares many of their same features. However, it does so with a crucial difference: the surfacing of the game’s algorithms onto the screen. Rather than a mere metafictional conceit, such surfacing tactically disrupts not only the all-powerful God illusion of many games, but also forms of critique bent on always digging deeper through an imagined hierarchy of screen, software, and hardware. Instead, for particular tactical games like else Heart.Break(), the flagrant display of the game’s own computational base superimposed on its representational superstructure suggests the possibility of the critical immersion and tactical construction of our own digital and analog worlds.

Why dig deeper when its all on the screen?

-

In addition to the manual, there are around 140 unique floppy discs in the game (as well as multiple copies of most). They contain everything from clues to poems to links for real websites to snippets of code to cocktail recipes. ↩︎

-

I’m also fairly certain that characters in the game hint at this possibility, but I’m currently lacking evidence (/looking forward to finding it over the holidays). ↩︎