From Liberal Arts to Data Arts: The New Dream for a Common Language

Posted on May 3, 2021

Prompted by the emergence of interdisciplinary data science programs at major U.S. universities, Alan Liu’s latest graduate seminar posits data science as the new liberal arts, a universal and totalizing form of knowledge that touches all disciplines, cultures, and histories. With this massive transition (or, more pessimistically, overhaul) of the liberal arts framework, data science fundamentally alters not only traditional disciplines of study but also and intrinsically, global power structures, economic modes, subjectivities, and forms of resistance/revolution. Without imposing a cause-and-effect relationship, this post ruminates on the emerging constellation of paradigmatic shifts from liberal arts to data arts and from the liberal humanist subject to the posthuman or cyborg, alongside transformations in the structuring and dissemination of knowledge.

But first, what were the liberal arts?

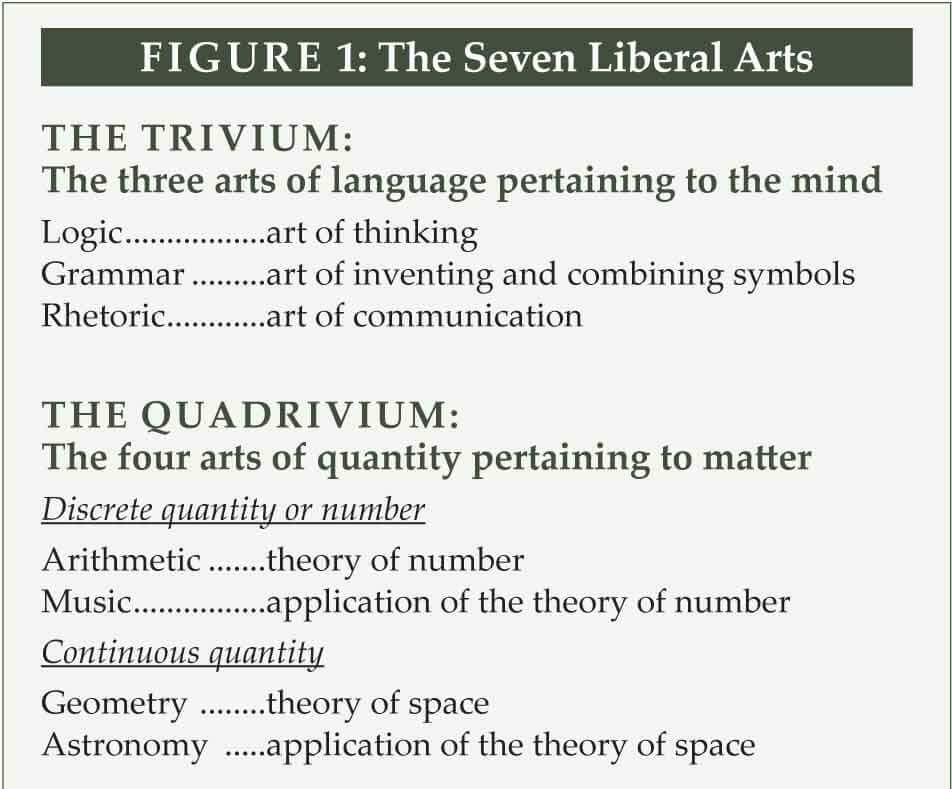

In “What Are the Liberal Arts?,” Sister Mariam Joseph diagrams the disciplinary structure of a liberal arts education, consisting of the Trivium (Logic, Grammar, Rhetoric) and Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Music, Geometry, Astronomy)—the former addressing the “arts of language pertaining to the mind” and the latter “the arts of quantity pertaining to matter.” Dating back to the Middle Ages, the liberal arts model has structured Western education for centuries, its seeming universality called into question recently with the emergence of data science. As Prof. Liu asked, “Where would data fit into this structure?” My answer, and I think the answer implied as the premise of the course, is that rather than fitting into the trivium or quadrivium “data” would radically usurp the model, replacing the “liberal” of “liberal arts” with “data”—that is, they would become the “data arts.” In other words, data does not merely alter our conception of a particular art (e.g. arithmetic)—instead it touches on every branch of the liberal arts and so significantly that each branch needs to be reformulated according to the impact of data.

But there’s perhaps an even more significant paradigmatic shift lurking beneath the replacement of liberal arts with data arts—that is, the omission of the term “liberal.” As Otto Willmann elucidates on the philology of the term:

“The expression artes liberales, chiefly used during the Middle Ages, does not mean arts as we understand the word at this present day, but those branches of knowledge which were taught in the schools of that time. They are called liberal (Latin liber, free), because they serve the purpose of training the free man, in contrast with the artes illiberales, which are pursued for economic purposes; their aim is to prepare the student not for gaining a livelihood, but for the pursuit of science in the strict sense of the term, i.e. the combination of philosophy and theology known as scholasticism” (Catholic Encyclopedia).

As implicit in Willman’s analysis of the term, the liberal arts were not only a form of structuring knowledge, but, as with all knowledge structures, a means of structuring power relations—in this case, dividing and hierarchizing the classes of the free and the unfree. As such, the liberal arts facilitated the class structure of society, in which the upper class could study the “immanent or intransitive activities” (Sister Mary Joseph)—or those universal to the human spirit—while those in the lower classes learned the illiberal or utilitarian arts, if they received any schooling at all.

In addition, the trivium/quadrivium division of the liberal arts reinforces the logic of yet another hierarchy, that of the the mind/body dualism, with the trivium addressing the mind and the quadrivium addressing matter. Although long before Descartes thought himself into existence, we can see here the beginnings of a liberal humanism, in which the mind is valorized not only over the body but over material existence itself, perfectly in line with Christianity’s (medieval or otherwise) rejection of the material world.

What happens to these dichotomies when the liberal arts gives way to the data arts?

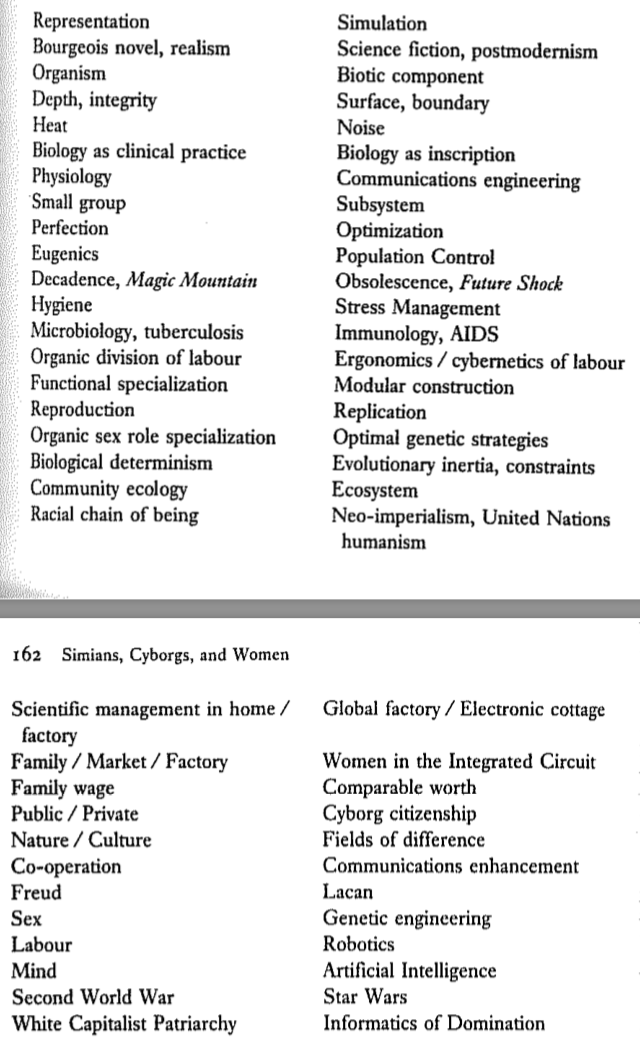

Perhaps, as a jumping off point, we might return (as I do, again and again) to Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” and its thorough demarcation of the shift from industrial (left column) to postindustrial society (right column):

Donna Haraway’s Diagram (161-2)

Donna Haraway’s Diagram (161-2)

Along with these paradigmatic transitions in aesthetics, biology, communication, warfare, and work, might we add a new one for education, with liberal arts on the left side and data arts on the right? It seems to me that such an addition provides crucial insight into how postindustrial subjects are disciplined into what Haraway calls the “informatics of domination,” but which certainly goes by other less ominous names as well: Late Capitalism, Postindustrialism, Neoliberalism, Network Society, Information Age, etc.

As such, we might think of the relationship between liberal arts and liberal humanism as giving way to that between data arts and posthumanism, of which Haraway’s revolutionary cyborg is only one possibility. As she herself admits, “From one perspective, a cyborg world is about the final imposition of a grid of control on the planet, about the final abstraction embodied in a Star Wars apocalypse waged in the name of defence, about the final appropriation of women’s bodies in a masculinist orgy of war” (154). Further evaluating the dystopian dimensions of the posthuman, N. Katherine Hayles elucidates a potential continuity between liberal humanism and posthumanism, in the denial of the body: “To the extent that the posthuman constructs embodiment as the instantiation of thought/information, it continues the liberal tradition rather than disrupts it” (5).

From these dystopian takes, one can perceive the transition from liberal arts to data arts, from humanism to posthumanism, not as an historical rupture but as a logical hyperextension of the former, wherein the rise of data science might break down the liberal arts divide between the trivium (mind) and quadivium (matter) but only to render it fully informational, leaving behind the materiality of human and nonhuman embodiment. Haraways calls it “the translation of the world into a problem in coding” in which “information is just that kind of quantifiable element (unit, basis of unity) which allows universal translation, and so unhindered instrumental power (called effective communication)” (164). Or, as the NYU Center for Data Science puts it: “Data science is the new language of the 21st century.” Perhaps the transition from liberal arts to data arts merely resurrects the phallogocentrism of the past, assimilating not only all human cultures and histories but nonhuman ones as well into the common language of data.

Another, more optimistic, possibility might lie in what Os Keyes has recently suggested but not yet thoroughly defined, a Radical Data Science “that is not controlling, eliminationist, assimilatory. A data science premised on enabling autonomous control of data, on enabling plural ways of being. A data science that preserves context and does not punish those who do not participate in the system.” We can hear in Keyes’ anti-assimilationist “plural ways of being” echoes of Haraway’s condemnation of phallagocentrism and the desire for a common language: “This is a dream not of a common language, but of a powerful infidel heteroglossia. It is an imagination of a feminist speaking in tongues to strike fear into the circuits of the super-savers of the new right” (181). If, as the NYU program advertises, data science is the “new language of the 21st century,” what heteroglossias might emerge to disrupt it, breaking down the circuitry of our global new new right? And how might the humanities, relegated to an optional domain emphasis, contribute to the cause?

Works Cited

Haraway, Donna J. “Cyborg Manifesto.” Simians Cyborgs and Women. Free Association Books, 1996.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. 1 edition, University Of Chicago Press, 1999.

Joseph, Sister Miriam. “What Are The Liberal Arts?” In The Trivium: The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric, 3–11. Philadelphia: Paul Dry, 2002. https://www.memoriapress.com/articles/what-are-the-liberal-arts/.

Keyes, Os. “Counting the Countless: Why Data Science Is a Profound Threat for Queer People.” Real Life, 2019.

New York University. “NYU Center for Data Science – Harnessing Data’s Potential for the World,” 2019. https://cds.nyu.edu/.

UC Berkeley. “Data Arts and Humanities,” 2019. https://data.berkeley.edu/degrees/domain-emphasis/data-arts-and-humanities.

Willmann, Otto. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1907. New Advent. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01760a.htm.