The Persistence of Canons in the Digital Humanities

Posted on March 25, 2017

But the trouble with close reading (in all of its incarnations, from the new criticism to deconstruction) is that it necessarily depends on an extremely small canon. […] And if you want to look beyond the canon […] close reading will not do it. It’s not designed to do it, it’s designed to do the opposite. At bottom, it’s a theological exercise—very solemn treatment of very few texts taken very seriously—whereas what we really need is a little pact with the devil: we know how to read texts, now let’s learn how not to read them. 1

Franco Moretti, “Conjectures on World Literature” (2000)

So why, a few decades after the question of canonicity as such was in any way current, do we still have these things? If we all agree that canons are bad, why haven’t we done away with them? Why do we merely tinker around the edges, adding a Morrison here and subtracting a Dryden there? What are we going to do about this problem? And more to the immediate point, what does any of this have to do with digital humanities and with debates internal to digital work? 2

Matthew Wilkens, “Canons, Close Reading, and the Evolution of Method” (2012)

One of the promises of digital humanities scholarship, going back at least to Moretti’s quote above, has been the potential, even the necessity, of moving beyond canons. Not merely The Canon (of dead white males), but canons in any form and of any composition—that is, any assemblage of literary texts with which scholars within a given field are assumed to have some familiarity if not expertise. But, as Matthew Wilkens points out, canons still exist, albeit in a slightly more multicultural variety. In this post, I would like to reopen the discussion of canons in the digital humanities, highlighting some of the ways through which they still exist and exploring the potential for moving beyond them.

But first, a brief (and no doubt incomplete) summary of the rather disparate critiques of the canon over the past 30 years. In the quote above, Wilkens observes that “we all agree that canons are bad,” but of course we don’t always agree on why. Much of the Canon Wars of the 1980’s and 90’s focused on the homogeneity of The Canon, criticizing its over-representation of white male authors and exclusion of those of other racial, gender, or class identities. From this perspective, the issue was not canons per se, but The Canon’s inability to reflect the multiplicity of identities in our multicultural society, and the solution most commonly involved either opening up The Canon to include more diversity or building alternative new canons to challenge its hegemony.3 Others such as John Guillory shifted the debate toward focusing on canons themselves as institutionally situated formations of cultural capital that always—no matter how diverse—reproduce social inequality between those who have and those who do not have access to them.4 For Wilkens and Moretti, however, the problem with canons exists in their relation to close reading. Wilkens and Moretti perceive the hegemonic practice of close reading as determining the institutional adherence to canons. Canons for them limit the scope of literary research, not only through excluding the great unread, but also blocking access to new research questions that arise when confronted with larger data sets. (As Moretti writes, “world literature cannot be literature, bigger; what we are already doing, just more of it. It has to be different. The categories have to be different.”) Thus, we might identify three main critiques of canons–the representational, the institutional, and the methodological (although, of course, there’s a fair bit of overlap among them), and each entails several different ways of solving the problem of canonicity. For the purposes of this post, I will only focus on this problem in relation to the digital humanities.

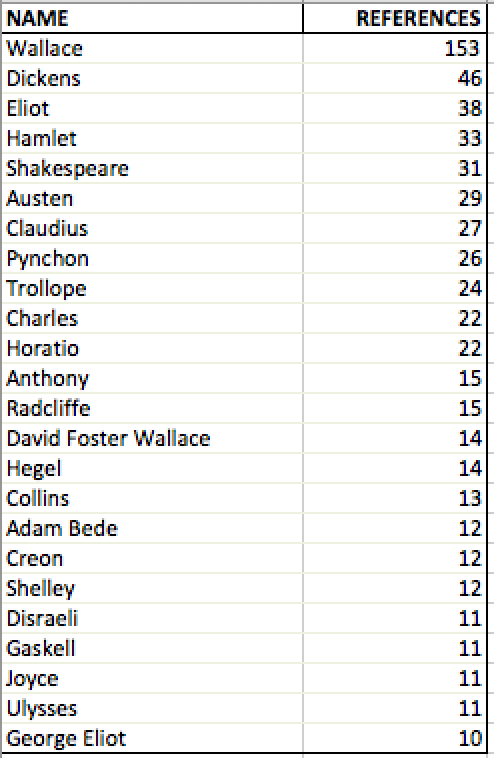

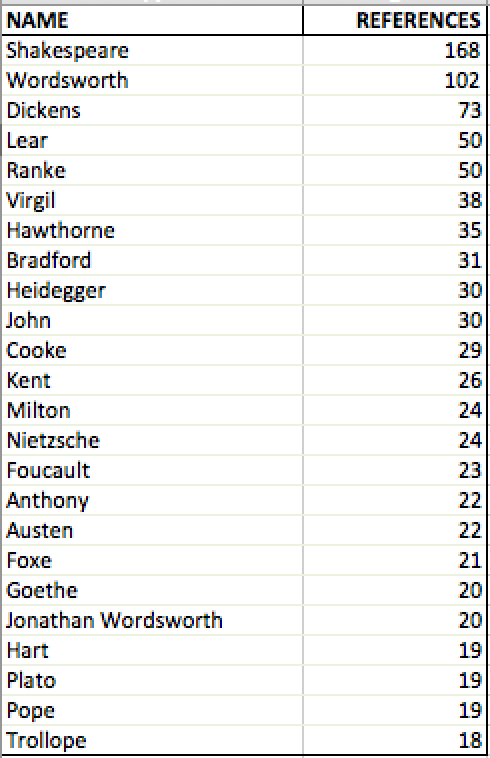

It’s been seventeen years since the publication of Moretti’s “Conjectures on World Literature”; how well have the digital humanities managed to move beyond a reliance on canons? Not very, at least so far as I can tell through some preliminary, and admittedly amateurish, digital investigation. In order to track the persistence of canons in digital humanities scholarship, I applied Stanford’s Name Entity Recognition software to two different corpora: the Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlets published to date (Left Image), and the assigned readings of a digital humanities course I took at Georgetown University (Left Image). After transferring the results to an Excel sheet, combining the multiple mentions in a pivot table, and removing the non-literary names, I developed the following lists of most commonly referenced names in these two DH corpora:

|

|

Obviously, there are quite a few issues with this process, both technical and methodological. For the former, some of the PDFs did not convert well into plain text files, requiring the removal of significant amounts of data. For the latter, the small sample sizes of each corpora could hardly provide sufficient evidence of the entire scope of the digital humanities. In addition, there’s the obvious observation that if an author were mentioned multiple times throughout a corpus, of course that author would retain (or perhaps, attain) canonical status. In order to address these issues, further study of canonical references in digital scholarship will require better tools and more comprehensive statistical analysis than I currently have at my disposal. Nevertheless, as preliminary and very tentative results, these figures suggest the persistence of canonicity (even and especially of The Canon) in digital humanities scholarship.

I want to suggest three ways (although there’s possibly many more) in which the digital humanities perpetuates canonicity: (1) projects that focus exclusively on canons, oftentimes The Canon; (2) continual reference to particular literary works (notably, science fiction and e-lit) that creates a new canon of the digital humanities; and (3) projects that apply digital tools to the extracanonical archive but still rely on canonical reference to explain their results. Generally speaking, critiques of the digital humanities canon-centricity revolve around the first tendency. Especially in the early days of humanities computing, the field mostly centered on applying digital tools to the analysis of major canonical works. Of course, this canonical approach to the digital humanities still exists, but it has also received enough criticism to leave behind for a moment here. In addition, the creation of new digital humanities canons will be left aside for now, though it’s most visible in the amount of critical attention given to books like Neuromancer and Patchwork Girl.

Instead, I’ll focus solely on how canonicity persists even in ostensibly extracanonical research that draws from large corpora of mostly noncanonical works. I started thinking about this tendency while reading Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac’s insightful Literary Lab Pamphlet, “A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method,” in which the authors develop and apply a digital methodology for analyzing the novel’s shift in theme from the beginning to the end of the long 19th century.5 In so doing, the authors were able to identify a decline in key words signifying abstract values (particularly ones associated with Victorian morality) over the course of the literary period. Although this study incorporated thousands of noncanonical works, as Literary Lab Pamphlet 11: “Canon/Archive: Large-scale Dynamics in the Literary Field” points out6, one could derive the same results by applying the these digital methods to only the 19th century canon. Further, the latter half of the article conceptualizes these results through recourse to a handful of canonical authors, representing the novel’s shift as the transition from Austen’s rurality to Dicken’s urbanity. Moving away from the dataset of 2,958 novels, the end of the article provides close readings of Wordsworth, Dickens, and Austen, illustrating not only that applying the same digital methods to the 19th century canon would have obtained the same results (as in “Canon/Archive”), but that one might have made the same argument without digital methods at all. In providing both distant and close readings of the long 19th century, the article raises an important methodological question for the digital humanities: what function might (canonical) close readings serve in the digital analysis of large corpora? Is there a way of combining close and distant reading–which many scholars have argued for7—without seemingly undermining the necessity of one or the other?

In attempting to answer these questions, we have to consider not only the cultural institutions that grant authority to canons (Guillory’s “school”) but also the technologies through which cultural meanings are transmitted and institutional power is mediated. If we are going to move beyond canons, clearly the transition to digital tools isn’t enough. Canons are neither purely the product of our cultural milieu nor of our technologies of reading. Instead, the canon emerges from the intersection between our cultural (perhaps even ideological) inheritance and the affordances and constraints of the material practices of storing, disseminating, and analyzing text. Despite adopting digital methods, we still rely in large part on references to canonical figures in order to render large-scale digital analyses intelligible or meaningful. For this reason, canonical close readings in Heuser and Le-Khac’s study above are not merely inconsequential to the argument. References to Dickens and Austen ground the theoretical implications of the digital analysis in culturally recognizable signifiers. Instead, we might think of these close readings as a skeuomorph easing the transition from one method of analysis to another, as we conjecture new means of cultural signification that leave the canon entirely behind. Digital tools provide the possibility for such canonical transcendence. But constant critique of their ontological and epistemological implications (their structuring of our world and our knowledge of it) is necessary in order to appropriately seize the means of critique, reshaping the literary landscape as non-canonical.

REFERENCES

-

Moretti, Franco. “Conjectures on World Literature.” New Left Review 1. Jan Feb 2000, 54-68. ↩︎

-

Wilkens, Matthew. “Canons, Close Reading, and the Evolution of Method.” Debates in the Digital Humanities. University of Minnesota Press, Web. 24 Mar. 2017. ↩︎

-

For an extension of this perspective into the digital humanities, see Amy E. Earhart’s “Can Information Be Unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon.” ↩︎

-

Guillory, John. Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1993. Print. ↩︎

-

Heuser, Ryan, and Long Le-Khac. “A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method.” Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlets 4 (2012): Stanford University. Web. 24 Mar. 2017. ↩︎

-

Algee-Hewitt, Mark, Sarah Allison, Marissa Gemma, Ryan Heuser, Franco Moretti, and Hannah Walser. “Canon/Archive: Large-scale Dynamics in the Literary Field.” Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlets 11 (2016): Stanford University. Web. 24 Mar. 2017. ↩︎

-

See, for instance, Katherine Hayles’ “How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine,” and Julie Orlemanski’s “Scales of Reading.” ↩︎